Where have all my colleagues gone?

An aging workforce in Germany, Japan, the US and UK is likely to decrease wealth by up to 15%

Michela Coppola

© Tom Sibley

They go quietly. By, more than seven million Germans – 20% of the labor force – will have left their desks and workbenches to retire (if labor force participation rates stay constant). Employers will struggle to find successors as Germany ages and its workforce shrinks.

Meanwhile, the number of consumers stays largely constant and the average amount of goods and services available per person will shrink – if productive structures, that is output per hour, hours worked and labor force participation stay constant. The question then is: Where will all the wealth come from?

SO WHAT TO DO?

Societies have three options to fend off the cost of aging. One is work longer; two is increase the productivity of workers; or three plug the demographic drain with formerly marginalized groups: women, the elderly and immigrants. But unless we make use of these options, the effects of aging will decrease the amount of goods and services available for consumption.

Societies need to rethink their concept of gainful employment to include older workers and women in the workforce, applying a blend of policies ranging from labor market to social security, health and education to be prepared for aged societies, or risk being unprepared for the onset of aging. Labor markets need to become more flexible to increase labor force participation and offer incentives to retire later. Workers’ productivity needs to be boosted through lifelong education, improved health and the use of technology to ultimately extend professional lives while addressing the particular challenges of older workers.

The US already suffers from declining labor force participation due to demographic change. “Aging of the baby boom generation explains around 50% of the near three percentage points labor force participation rate decline during,” Ravi Balakrishnan and colleagues write in Recent U.S. Labor Force Dynamics: Reversible or not?

Methodology

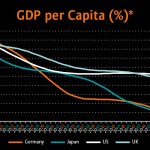

Gross domestic product per capita from, the most recent data available, was used as a measure of well-being. It indicates the total amount of goods and services produced in one year and divides it by the nation’s total population. Thus it gives a sense of how much is available for consumption to every person in an economy.

Please note, that the workers represent only a share of those of working age as not everybody aged 15 to 64, the standard definition of working-age population, is necessarily gainfully employed.

Output growth declined since and was further weakened by the financial crisis, the International Monetary Fund reports in its outlook Uneven Growth: Short and Long-Term Factors .

The future, as the IMF sees it, does not look particularly bright either. “Potential growth in advanced and emerging market economies is likely to remain below precrisis rates. In advanced economies, potential growth is expected to increase only slightly from current rates.” The IMF cites aging populations and an only gradual increase in asset growth as the main reasons. In emerging markets, potential output growth will decline further due to aging, lower investments and lower total factor productivity growth.

So where have all your colleagues gone? Retirement has picked them everyone, Pete Seeger might have responded.

Societies need to adjust to aging, but the question is how? Our economists Michela Coppola and Richard Wolf discuss three approaches in forthcoming articles on productive structures.

To understand the impact of aging on productivity in Germany, Japan, the US and UK, International Pensions calculated the decrease of the labor force until. The productive structure – hours worked, output per working hour and labor force participation – was assumed to stay constant while populations age as projected by the United Nations.

To understand the impact of aging on productivity in Germany, Japan, the US and UK, International Pensions calculated the decrease of the labor force until. The productive structure – hours worked, output per working hour and labor force participation – was assumed to stay constant while populations age as projected by the United Nations.